Seaside tourism has long been a cultural fixture in Britain. John Urry discusses British seaside towns emerging in the 19th century as a healthful retreat for the upper classes. Then in the 20th century those seaside resorts gradually became more accessible to everybody. Places like Margate, Brighton, and Blackpool were transformed into bustling hubs of leisure. Complete with donkey rides, amusement arcades, and promenade photography. The beach became more than a holiday destination; it was a shared social ritual, deeply embedded in the national psyche.

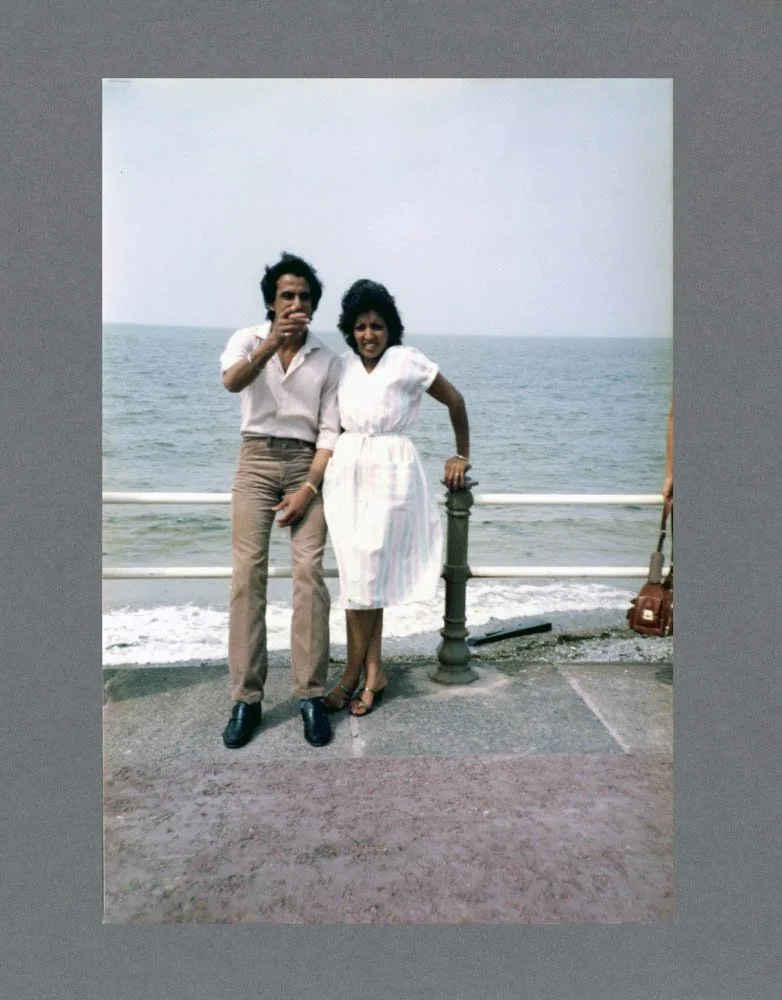

Figure 1: Bhajan Kaur, Blackpool c.1985

Photography played a central role in this ritual. Families captured their outings in posed portraits or spontaneous snaps, cementing the seaside as a space of memory, belonging, and identity. Holiday photos weren’t just souvenirs; they were declarations of participation in a cultural tradition; material proof of a life lived in step with national rhythms.

For many postwar migrants, including South Asian settlers from Punjab, participating in this visual culture was a way to navigate the unfamiliar contours of British life. The Apna Heritage Archive houses hundreds of photographs taken by Punjabi families at various British seaside resorts. These images reveal how these communities embraced the seaside as both a leisure space and a performative stage of belonging.

One such image captures this dynamic beautifully.

Figure 2: Joginder, Satinder, Monica and Narinder Phokela, Blackpool c.1976

A sun-soaked beach bustles with the easy chaos of a British summer holiday. Amid rows of deckchairs and scattered beach towels, a Punjabi family anchors themselves in the sand. A man in a light blue turban reclines shirtless in a red-striped chair. Beside him, a woman in a bright floral sari rests her arm gently on her handbag. Around them, children play in the sand. A blonde child joins them, a sign of playful mingling on a communal beach.

Behind them, dozens of holidaymakers. Sunbathing families and strangers stretch along the shore in shared leisure. The scene is unmistakably British: the classic deckchairs, the concrete promenade with its white and blue balustrade, the terraced buildings overlooking the sea. But the photograph also speaks to something deeper. A quiet assertion of cultural presence. This family, dressed partly in traditional clothing, partly in swimming trunks and sandals, has laid claim to the sand not as outsiders, but as full participants in a national ritual.

Photography here becomes an act of agency. By taking and keeping these photos, Punjabi families inserted themselves into a visual narrative from which they were often excluded. They reframed the beach, not as a relic of Britishness, but as a shared reimagined space. As scholar Marianne Hirsch reminds us, “Family photographs are not just images of the past, they are instruments of memory and identity; they help us narrate who we are, where we came from, and how we belong.”

Figure 3: Pradeep, Jasvinder, Sandeep and Sukhvir Kalsi, Cornwall c.1986

Crucially, these photographs do not act in isolation. Martha Langford argues in her essay; family photo albums are not static records but dynamic performances of memory. They gain their full meaning not from silent viewing but from being spoken. Narrated by parents or elders, who layer them with stories, emotions, and cultural significance. In Langford’s oral-photographic framework, the family album becomes a medium through which diasporic identity is continuously shaped and shared. For these Punjabi families, the seaside snapshots are not merely documentation of assimilation. They are staged conversations, passed across generations to affirm continuity, place, and belonging.

Figure 4: Bhajan Kaur, Blackpool c.1985

In an era when public discourse around migration was often fraught, these ordinary moments of joy and integration carry extraordinary significance. They challenge monolithic ideas of what it means to be British and remind us that belonging is not only legislated from above but lived and documented from below.

Figure 5: Christine Shutt with Pradeep, Rhyl, Wales c.1981

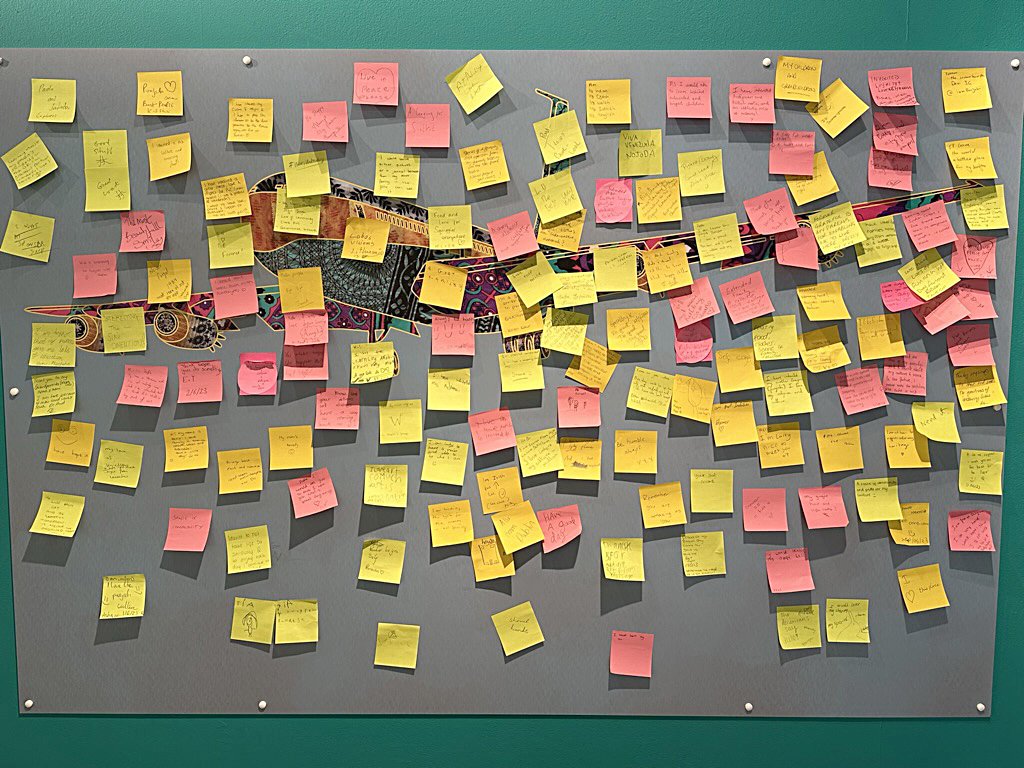

The beach, once a symbol of imperial leisure and native nostalgia, becomes in these photos a site of plural identity. Archives like Apna don't just preserve history. They offer a richer, more inclusive way of seeing who shaped modern Britain.

These photographs are more than snapshots—they’re fragments of lived experience, woven into the broader story of migration, memory, and belonging in Britain. If this glimpse into the lives and memories of Punjabi families by the sea has sparked your interest, we have curated an online exhibition featuring many of the family images from the Apna Heritage Archive which can be found here:

https://www.bcva.info/online-exhibition-british-punjabi-staycations

Bibliography

Hirsch, Marianne. Family frames: photography, narrative, and postmemory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997. https://archive.org/details/familyframesphot0000hirs/mode/2up

Langford, Martha. "Speaking the Album: An Application of the Oral-Photographic Framework." In Locating Memory: Photographic Acts, edited by Annette Kuhn and Kirsten McAllister, 223-246. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2006. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781782381990-012/html

Urry, John. The Tourist Gaze. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications, 2002. https://archive.org/details/touristgaze0000urry/mode/2up